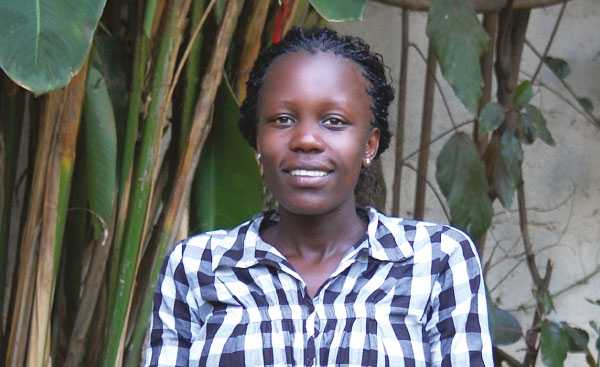

BEATRICE OYOMBE Lessons learnt from my ABORTION

Teenage pregnancy is considered a taboo topic in many homes. It is often discussed in hushed tones and shrouded in secrecy. Not so for 24-year-old Beatrice. She is not afraid to talk about this delicate subject especially when her audience is made up of young girls in high school. She has amassed this courage over the past one year and it only came after sharing her story with fellow post-abortive girls and women. She takes WANGARI MWANGI through her journey of rejection, denial and recovery from her unplanned pregnancy.

Beatrice, a rather quiet and laid back person, describes the relationship with her mother and elder sisters as distant. According to her, the women in her life appeared too busy to have time for her when was going through a crisis in her life and as such she cannot boast of having a close relationship with them.

“I think everyone was caught up in the hustle and bustle of fending for themselves after high school. My sisters moved to Nairobi immediately after competing high school, so we never got to bond much. Mum, on the other hand, was always busy trying to fend for my two younger brothers and I and also making sure we received some decent education,” says Beatrice who hails from Kisumu.

Veering off track

School fees was the only thing standing in Beatrice’s way to becoming a doctor, a desire she still clings on to this day. Her father passed on when she was eight years old leaving her and her six siblings under the care of her uncles and struggling mother.

“Proceeds from mum’s business was only enough for our basic needs and she could only do so much. One of my uncles proposed that I make a second attempt at the Kenya Certificate of Primary Education (KCPE) with the promise of paying my school fees. But soon after the release of the 2007 KCPE results, he appeared to have changed his mind. He grew cold to the idea of sponsoring my education,” recalls Beatrice.

The sudden change of heart saw her spend three quarters of the first term of school at home helping her mother with her farming business with the hope of raising some money to join any local high school. She got a slot at a mixed day high school close to her home in Kisumu. “Two of my elder sisters had gone through the school and had left an enviable record. I borrowed some old uniforms from an old girl of the school and I enrolled,” she says.

Beatrice settled well in school and was even appointed the games captain due to her prowess on the track. Her academic performance was also promising. Despite joining the school late, her grades at the end of the term were outstanding. Beatrice had begun her high school education on a high note. It was in the midst of this glory that her chemistry teacher took notice of her and approached her. “He seemed to know so much about my sisters and my background. His generosity surprised my mother and I, especially when he volunteered to buy me textbooks and chip in paying my school fees. He was young, but I treated him like a father figure. My mother too had a lot of respect for him,” she says.

By the end of her first year in high school, she had been lured into a relationship with him. Beatrice admits being very close to the teacher to the extent of having the spare key to his house. They were, however, discreet enough to hide it from the school administration, other students and her mother. The relationship with her teacher soon turned intimate. Beatrice confesses to having several sexual encounters with him in his house. They did not bother to use protection.

“At the time I was so naïve. I thought because he had been generous to show interest in my education, accepting to get intimate with him would be a good way of returning the favour,” she says adding that her timid nature held her back from saying no to his sexual advances, as she feared disappointing him.

Beatrice learnt she was pregnant as she was writing her form three end-of-year examination papers. The news befuddled her teacher-cum-boyfriend who immediately proposed an abortion. “He reasoned that pregnancy would mean I put my education on hold for a whole year or end it all together. He argued that if I carried the pregnancy to term, I would miss my chance of sitting for the Kenya Certificate of Secondary Education (KCSE), and this would be disappointing for my mother who had put in so much effort into paying for my education,” she recalls.

After weighing her options, she agreed to have an abortion by suction method – a painful process that took four hours to complete. By the time she underwent the procedure, she was one and half months pregnant. She never said a word to her mother. A week after the abortion she found out that the teacher moved out to a new estate. Their communication became strained and he would not bother to answer her text messages or phone calls. This wasa clear sign that he no longer wanted to be associated with her. Beatrice says he even deliberately lowered her marks in the last chemistry examination paper and, to add salt to injury, put the remark: “poor student.”

The trauma of abortion

The soured relationship with her teacher and abortion came back to haunt her during the long December holidays. She developed a negative attitude towards men who she says reminded her of her chemistry teacher. And as January edged closer, she feared going back to school lest she bumped into her teacher. She asked her mother to transfer her to a boarding school so that she could concentrate on her studies.

“I had to hatch a plan that would not raise suspicion. I was confident that if I told my mother that I wished to repeat form three to improve my performance and chances of getting good grades in the final examination, she would readily agree,” she says.

Her prayers were answered and her mother bought to the idea. She secured a place at Bishop Mwai Abiero Magwar Girls Secondary School, a boarding school. She opted to repeat form three. Due to her financial background and excellent performance, the school listed her for sponsorship. But even then, the ghost of abortion continued to haunt her. Her concentration levels for all the subjects taught by men went down. For Beatrice, all male teachers resembled the chemistry teacher who had made her pregnant and then rejected her.

The secret of her abortion spilled out in 2011 after her botched suicide attempt. She sneaked out of school and went looking for the chemistry teacher on a revenge mission. Beatrice says that she broke into his house and ingested pesticide hoping the teacher would feel hurt by her death in his house. “I wanted him to experience the same pain he had taken me through by taking advantage of me, then rejecting and ill-advising me to have an abortion. When I came to, I was in a hospital bed with my mother and sister by my side. I had no option than to tell them the truth,” says Beatrice adding that they did not sue the teacher and preferred to drop the matter all together since she also had a part to play. “My mother was very disappointed in me and the teacher. Due to my then secretive nature it was hard for them to establish whether I was coerced or it was by free will that I agreed to have an intimate relationship with the 30-year-old teacher. He had also chipped into my education and I guess this also made it hard for my mother to sue him,” she says.

Starting out afresh

After the incident, the school took her for counselling classes, which helped Beatrice cope during her last year of study. One of the key lessons she learnt was that of forgiving herself. Although the psychological trauma had already impacted on her academic performance, she still registered for KCSE.

Beatrice moved from Kisumu to Nairobi after her KCSE in 2012. Her former headmistress at Bishop Mwai Abiero Magwar Girls Secondary School paid for her computer training to keep her busy as she awaited the release of the KCSE results. Her brother, a gym instructor, also enrolled her to train as a gym instructor just to keep her occupied and to help her become self-dependent.

“These two activities kept my mind preoccupied and it got even better when I secured a well paying job at a gym in South C estate. I was able to afford my own apartment. As had become my nature since the abortion, I continued keeping to myself for fear of being judged,” she says.

It was in the course of her work that a client noticed that Beatrice kept to herself and enquired if all was well with her. When Beatrice opened up to her, she referred her to Pearls and Treasures, a post-abortive recovery centre based in Nairobi, for counselling. After the three-months’ session, Beatrice says she felt encouraged to share her story with others as a way of healing.

“It is therapeutic for me as a post-abortive woman. Talking about it gives me a chance to exhale and reconcile with myself after taking in so much blame. I also talk about my experience because there are some young girls in schools who need to be forewarned about the dangers of engaging in unhealthy relationships that may lead to early and unplanned pregnancies,” she says. She also adds that mothers should cultivate a close relationship with their daughters as this will help in their communication and make it easy to discuss incidents such as relationships before they degenerate into serious consequences like hers.

Published in March 2015