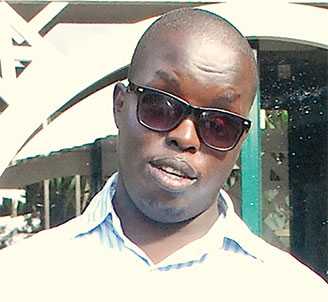

MUGAMBI PAUL Transcending the disability barrier

Mugambi Paul is impact-oriented, passionate, confident and persistent. He never gives up easily. He is also blind and refuses the visually impaired euphemism to describe his condition. He fondly refers to himself as “Mpofu Number One.” Rather than take his condition negatively, he takes it as a positive challenge to reach greater heights. He shared his experience with MWAURA MUIGANA.

It is Monday, October 27, 1987. Mugambi is playing with friends on the road just outside his home in Meru. Some people are passing by and there is a sudden commotion. He is caught in the melee and a fist lands straight on his face. His eyes are gravely injured. He lies on the ground bleeding as excruciating pain runs through his head.

His parents and good Samaritans rush him to hospital. The doctor examines his eye and as fate would have it, gives the wrong diagnosis and consequently wrong medication. Mugambi becomes totally blind and darkness becomes his friend for the rest of his life.

No one wants to believe this eventuality – not his family, not his friends and not even the local community. His parents are pressured to seek help from traditional healers including herbalists but none of their concoctions provide the much-needed cure. Desperation creeps in. Society exerts pressure on the parents; they are not doing enough for the boy. They are pushed to witchcraft. Nothing.

The distressed parents almost break down but decide to give it another shot. They turn to prayers but there was no cure in sight. Then they turn to a famous preacher who had taken the country by storm through televised healing crusades. This is their last resort.

Mugambi takes his turn at the podium joining the lame, blind and sick for the healing miracle. They are prayed for and assured the miracle is just about to happen. He can hardly follow when the preacher starts to speak in tongues.

He holds his breath, his heart pounding a tad too fast. He waits in anticipation for his miracle. Nothing. The preacher’s spanner boys are pushing the sick and asking them to fall on the ground and pretend the healing bug has bitten them. Mugambi refuses to go down because he has not received his healing. He is chided for lacking faith and is shown the door.

Finding solace in self-acceptance…

After all the fruitless effort, Mugambi finally resigned to fate and accepted that he would never see again. Life had to move on, many adjustments and new friends had to be made. He became positive, prayerful, pro-active and started the adjusting process. It wasn’t easy, but he managed.

He embraced braille so that he could continue with his education. This paid off handsomely as he passed the Kenya Certificate of Primary Education (KCPE).

He then joined Salvation Army High School for the Blind in Thika town where his positive outlook in life inspired his fellow students. He performed exemplary well in the Kenya Certificate of Secondary Education (KCSE) and joined Kenyatta University (KU) hoping to pursue a bachelor’s degree in law or communication.

Challenges abound…

That wasn’t to be. The challenges for him and other blind students, and indeed all disabled students, sprung up immediately he stepped into the university.

“Blind students then were not allowed to pursue courses of their choice. They were mainly crammed in education where I was pushed. I realised it wasn’t a coincidence that most blind persons were teachers. As if that wasn’t bad enough, there were no books in braille or audio materials. You could only read when you had a volunteer to read for you to get the information. It was very challenging but we survived,” he explains.

The college and its physical structures like lecture rooms and pavements were inaccessible to persons with disabilities. He discovered that his colleagues with disability had low self-esteem and thus shied from demanding their rights.

“These are some of the things that pushed me to join student leadership, which would give me the platform to advocate for the rights of student’s with disability,” he explains.

He was elected student leader representing persons with disability at the KU parliament known as congress. He got the opportunity to engage leaders and advocate for the agenda of persons with disability, and ensured that policies and strategies brought in by the university were friendly to this group.

His advocacy was not limited to meetings with the university administration. He engaged the then Joint Admission Board and ministry of education to push for the disability agenda. A lot was still at stake by the time he was graduating in 2006 but he was happy he had started the conversation. All was not in vain. In 2010, Kenyatta University started the process of making its campuses disability friendly.

“The then Joint Admission Board, now Kenya Universities and Colleges Central Placement Service (KUCCPS), was not left behind; currently, the minimum university entry point is a C plus for students with disability. They also take courses of their choice as long as they meet the requirements. Accessibility in terms of communication has improved with the introduction of some computer programs for the blind,” he says.

Life in the job market…

Like many other young Kenyans, he started job hunting upon graduation. It was more challenging for him due to his disability but he was determined to work and prove his mettle.

He sent out 485 applications to different organisations, most of which were unwilling to take blind persons on board. Some offered him a telephone operator’s opportunity regardless of his qualification.

His worst experience was with one of the communications companies in 2007. He attended an interview and in spite of being visibly blind, he was presented with pen and paper for a written interview. He protested and they promised to organise a special interview, a promise they didn’t honour.

“I had an altercation with the human resource officer and I threatened to file a discrimination suit against the company,” he recounts.

Mugambi is happy that the company later launched an audio program at the Braille Centre in Nairobi, and the CEO announced they would henceforth employ persons with disabilities. They currently have low vision and physically disabled persons within their workforce. He hopes they will soon start employing totally blind persons.

The discrimination was not just confined to the job market. He recalls dating a girl in campus whose parents rejected the relationship on the basis of his condition. She called off the relationship.

All these experiences taught him that nothing would come his way and that of other blind people on a silver platter. He resolved to always create space where there was none.

Advocating for persons with disability…

“The lesson I learnt and my advice to persons with disabilities and those without is that in this world, you have to create a space where there is no space. No one is willing to give you the opportunity if you don’t want to go out and look for it,” he makes a clarion call.

He decided to combine his job with advocacy. He joined the disability movement and became a board member of the umbrella organisation – United Disabled Persons of Kenya. He also joined the Kenya Sports Association for the Visually Impaired and served as the national vice chairperson.

He later joined both the Blind and Low-vision Network and Life-skills Promoters where he specifically brought on board concerns of persons with disability and visually-impaired.

He also participated in several policy registrations both locally and internationally when the government was pushing for the ratification, review and signing of the UN Convention for Persons with Disability.

In 2008, he resolved to get a job in the humanitarian world and was employed by an international non-governmental organisation, Handicap International. He became the first blind humanitarian worker at the Daadab Refugee Camp. He helped organisations in the humanitarian field to have their policies, strategies, projects and practices disability friendly.

He also helped the disabled access services, information through braille or audio format and employment opportunities, as well as working with community leaders to understand issues of disability and ensure representation of persons with disability is realised.

Early this year, he joined the government to work with the National Council for Persons with Disabilities as the regional coordinator for Nairobi. He deals with issues of advocacy, influencing access to facilities and for policies to be more inclusive.

He also deals with empowerment of persons with disability through referrals for jobs and support programmes in form of economic and education assistance.

Mugambi is also a singer and he uses this platform to highlight issues of disability while relating to real life experiences. His stage name is Mpofu Number One. He is currently pursuing a Masters degree in peace and conflict studies.

Recognition…

In 2013, Mugambi won a humanitarian award – Disability Champion by Christophe Blind Mission, an international NGO for being the first blind humanitarian worker at the Daadab Refugee camp. In 2014, he won Lifetime Achievement Award and in March 2015 won the Malaika Artist Award for the Activist of the Year for his inspirational music on disability.

He encourages blind people to use the white cane since it’s their lifeline. According to him, many blind people shun the cane to avoid being identified as blind.

“Many blind persons are not able to be proactive and adjust to life fast. When blindness hits you, accepting the situation is the first step to moving forward. I personally take life positively and try to live as normal a life as anybody else. I preach positivity about having disability and tell fellow blind persons there is nothing wrong with being blind and the sooner they embrace that, the better,” concludes Mugambi.