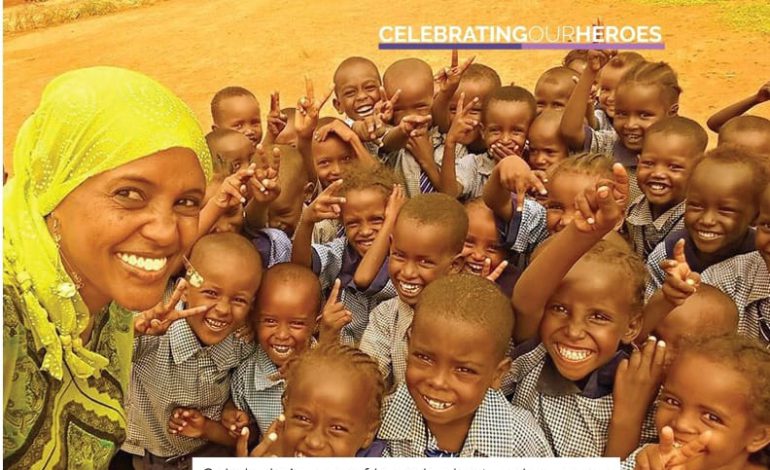

Qabale Duba: Meet award-winning nurse who is a beacon of hope for Marsabit girls

Qabale Duba came within whiskers of child marriage, was subjected to female genital mutilation (FGM) and had to put up a real fight to be allowed to complete her education.

Qabale Duba came within whiskers of child marriage, was subjected to female genital mutilation (FGM) and had to put up a real fight to be allowed to complete her education. She shares with AUDREY AWUOR her commitment to holding the torch of empowerment and education high in her community to light up the paths of other girls so they won’t have to walk in the darkness she walked through.

Qabale Duba has seen and experienced first-hand what lack of girl-child empowerment can do to a woman and a generation for that matter. Talk of poverty and period shame, lack of education, early marriages, FGM, domestic violence – she has seen and heard it all. At a tender age and growing up in the small Torbi village in Marsabit County, she was subjected to female genital mutilation – as was the norm in her community. For most communities in northern Kenya, this often is a precursor to marriage.

If any attention was paid to education at all, the boys were given the first priority. Her father was a staunch believer in the notion that girls ought to get married and make good wives. In fact, by the time she was done with class eight, she had already been engaged – without her knowledge. Her mum leaked her father’s plan to marry her off and she in turn reported the matter to her teacher. With the help of her brother, the marriage plans were called off.

“My mother was illiterate but she never wanted me to lead the life that she led. For someone who had never interacted with books, she had so much faith in education. She even used to wake me up to study when I was just in class four,” she says.

Opposing her father in itself was not easy work. He was a man who was known for his temper and penchant for beating up his wives. So bad was it that out of the eight wives he married, only three stuck with him, bearing him 19 children in total. Qabale’s mum was the first wife, and she was the last-born of her nine kids.

A village of no dreams

Few girls dared to dream beyond the humdrum Torbi village life. In such a community, daring to dream equaled to setting oneself up for failure and heartbreak. It was easier to just go with the flow of things than to go against the grain. But Qabale knew that education would be her only saving grace so she worked hard to not only be successful in life, but also give her father reason to keep paying her school fees.

She would emerge first in her class in primary and later on the second best in in her high school, where she got a B. She ended up being the first girl from her village to go to university when joined Kenya Methodist University for a nursing course. This alone showed all the other girls in her village it was okay to dream and when those dreams were backed, they compounded success.

In 2013 whilst in university, Qabale contested for and won the Miss Tourism Marsabit County beauty pageant. This, too, came with its set of challenges considering modelling was equated to nudity, which was against her community’s and religion’s fundamental beliefs.

“I proved them wrong by competing in my communities’ traditional outfits throughout the competition and representing our culture in the best way that I could,” she says.

Ending period shame

After the beauty pageant and having made a name for herself in the national pageant, she partnered with her county government in a sanitary towels distribution program she dubbed Pads and Pants (PAPA). This project was very close to her heart because her first experience with her menses was brutal.

“I was only twelve then and nobody had ever spoken to me about periods. When I started experiencing stomachache and discomfort, I thought I was ill. Little did I know those were period cramps,” she narrates.

When class was over, Qabale was the first to leave the classroom only for the boys in her class to burst into fits of laughter. She had soiled herself and did not have the slightest idea.

“I was so embarrassed. I missed school for a whole week to get over the experience.”

But that was not the last time she missed school for a week. This was a cycle that was repeated every month, not just for Qabale, but also for all the girls who had their menses. They feared soiling themselves and it did not help that they had no sanitary towels and had to resort to using cotton wool and other unsanitary supplements. These could leak thus avoiding school altogether saved them from embarrassing situations.

That was not all. “Even grown women did not have pants that is why I had to resort to distributing pads alongside pants to school-going girls and grown women, too,” she explains.

Her PAPA initiative introduced a more sustainable approach to end period shame – reusable pads. These could at least last the ladies up to a year because all they had to do was wash them after use.

“When it became too expensive to source them, I made plans to start a local plant that makes reusable pads from locally available materials,” she says.

Birth of Qabale Duba Foundation

The success of PAPA led her to start her own foundation – the Qabale Duba Foundation (QDF) so as to have a better reach and do more for her community. The foundation has now added maternal health education, access to education, mentorship programs, championing against harmful cultural practices, health, peace initiatives and economic empowerment, to its activities.

They have had to be strategic in their approach to fighting harmful practices such as female genital mutilation. This is a practice that almost 90 per cent of the girls are subjected to and campaigning against it can earn you opposition even from the women themselves. The practice is often done by traditional birth attendants (TBAs) and they, therefore, make the best agents of desensitisation of the practice.

“We have recruited the TBAs to educate people about the negative ramifications of FGM. They offer alternative rites of passage to the girls and advocate for girls’ education as opposed to early marriages that usually comes after FGM,” she says.

Working with traditional birth attendants also helps them reach their maternal health agenda. Many pastoralist women still choose to deliver at home, which puts the lives of both mother and child at risk. Sometimes this has to do with the distance from their homes to the available health facilities. The TBAs have undergone training under QDF, such that if they ever have to help women deliver, they do it in a safe, hygienic way. If not, they advise the women against home births.

“Because of FGM, childbirth can lead to complications such as fistula. The TBAs help as they identify women who suffer from these complications and who are at risk so we can help them access appropriate medical care,” she expounds.

QDF bridges the gap between warring communities in northern Kenya using women and youth as peace agents. This is done through yearly celebrations of international peace days in different areas which brings together different communities. They also do peace marathons, peace tournaments and peace mentorships among youths and women.

The mentorship program works with young professionals from local communities who go around the schools to mentor students using their own life stories and successes. The program also provides career guidance to both primary and secondary school students.

“As part of the mentorship program, QDF does opportunity awareness outreaches to youths and school leavers. We motivate youths to try different available opportunities like scholarships, fellowships and also conferences both locally and abroad. We mentor youths to take part in entrepreneurship so that they can be able to create job for themselves and also other youths who are jobless,” says Qabale.

For her relentless efforts in making her community better and improving the quality of lives of the women and girls in her county, Qabale has received award after award. In 2016, she was picked to participate in the Mandela Washington Young African Leaders Initiative and early last year, she received the Dada of the Year award from the Akili Dada Foundation. In June the same year, she was among the Top 10 finalists for the Global Citizens Organisation award, which is given to individuals and organisations from around the world committed to ending extreme poverty and its many causes and consequences

She was the first runners-up in the Diversity and Inclusion Awards and Recognition (DIAR) 2019 for the Gender Equality Champion Award. The award recognises and celebrates individuals and organisations that champion for inclusivity of people abled differently, youth, gender, peace and cohesion. She also won the Zuri Awards 2019 (Education Category) in recognition of her foundation’s work on literacy programme among children and women back in her village in Torbi, Marsabit.

Having achieved all these, there is still one way Qabale wants to go and that is forward.

This article was first published in the January 2020 issue of Parents.