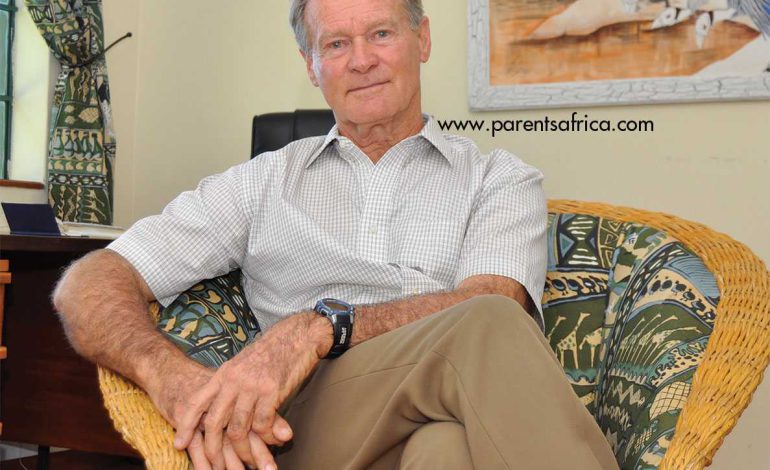

Dr David Western, Advocate of wildlife conservation

Dr David western, 72, is a dedicated conservationist. For over 48 years, he has pioneered research and community-based animal conservation strategies in East Africa and was among the first scientists to recognise the limitations of national parks and investigate how humans and wildlife can coexist. ESTHER KIRAGU had a chat with the man whose pioneering community-based conservation work has served as a model for finding a place for wildlife beyond parks around the world.

Dr Western, the son of a settler, retraces his passion for wild life conservation to his growing up days in Tanganyika, now Tanzania. “My dad was invoved in bush hunting in the 50s before realising that wildlife was in trouble and subsequently got involved in wildlife conservation by becoming a game warden,” he says.

A thrilling childhood best describes Dr Western’s early life, as he and some friends would occasionally sneak from school in Kongwa, Tanzania, to go hunting. These escapades earned him the nickname Jonah.

Dr Western was aware of his passion for wildlife and nature early in life. On completing his high school education, he travelled to the UK and enrolled for a Bachelors degree in zoology despite getting a scholarship to pursue a PhD in Britain, he chose to undertake his PhD in zoology at the University of Nairobi (UON) in 1967.

“I was among the first Kenyans to study for a PhD in zoology at the time. I chose to pursue my studies in Kenya because the university gave me the liberty to study the relationship between human beings and animals as opposed to studying animals only, which many other universities felt was the real zoology course. Having grown up in Tanganyika, I had understood that in Africa wildlife and human beings coexisted and so I wanted to understand this better,” explains the founder and chairperson of the African Conservation Centre (ACC) in Nairobi.

Enormous contribution to conservation… Dr Western spent four years doing research and learning about livestock from the Maasai at Amboseli in the late 60s, a decade before it became a national park.

This experience formed his research thesis as he learned what the Maasai already knew – that while cattle grazing was believed at the time to lead to the destruction of land and wildlife, wildlife were most abundance where the Maasai still practiced their age-old traditions of migrating with the seasons.

“These findings helped shape my outlook to wildlife conservation and I became a leading advocate for community-based conservation, which involved communities benefiting from and conserving wildlife on their lands,” he says. Based on his success at Amboseli, Dr Western was hired by the New York Zoological Society and the Kenyan government in 1977 to guide and oversee the plan to have Amboseli adopt the community-based conservation approach.

“Within a year of the plan’s establishment, the community around Amboseli had changed its attitudes towards wildlife. By the time the worldwide ban on ivory sales came into effect in 1990, the number of elephants in Amboseli had increased sharply. Migratory populations of zebra and wildebeest doubled in the decade following the enlistment of the Maasai community in wildlife conservation,” he explains.

He says research has shown that today, at a time when ivory poaching is a threat to elephants in Africa, the recruitment of landowners remains the most effective tool in conserving elephants. David’s work continues to serve as a barometer of changes on the land and a test of conservation solutions based on the coexistence of human beings and wildlife.

Dr Western went on to establish Kenya’s Wildlife Planning Unit, chaired the African Elephant and Rhino Specialist Group, and was founding president of the International Ecotourism Society.

He also directed the international programs of the Wildlife Conservation Society. In addition, he was chairman of the Wildlife Clubs of Kenya for many years and is now its patron. These successes saw David appointed to serve as director of the Kenya Wildlife Service (KWS) by retired president Moi in 1994.

“I launched various initiatives, which include Parks for Kenyans, which lowered citizen’s park entry fees and subsequently promoted local tourism. This led to a five-fold increase in domestic tourism,” he explains.

Other initiatives he helped launch include Parks Beyond Parks, a movement to promote communities setting up their own wildlife sanctuaries and enterprises; training and equipping community wildlife scouts; and the establishment of the Nairobi Safari Walk, whose aim is to educate young Kenyans in conservation.

Setting up the African Conservation Centre … Dr Western helped set up the African Conservation Centre (ACC) in Nairobi to formally engage and train African nationals in all aspects of conservation.

ACC has to date overseen over 35 Masters and PhD studies in conservation; set up many community-based organisations and non-governmental organisations and promoted their efforts. He is happy with the organisation’s accomplishment over the last 25 years. For instance, in 2015, ACC, commissioned by the Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources and Regional Development Authorities of the Government of Kenya, brought together national agencies, universities, non-governmental organisations and academic institutions to create a detailed assessment of Kenya’s biodiversity and launch a biodiversity atlas. Dr Western has also served on a government task force on redrafting the environmental legislation in line with the 2010 Constitution of Kenya.

He recalls incidences of increase in wildlife poaching in the 80s and says it was not until the prices of ivory came down that the country was able to see a decrease in poaching.

“In 2008, when the price of ivory rose steeply again elephants were under threat once more. Together with other conservationists, we helped bring the Tanzanian and Kenyan government agencies, community based organisations and other NGOs to work together to save elephants in and outside parks along the common border of the two countries. ACC drew up a joint programme to monitor elephant movements and deter poachers using community scouts. These efforts saw poaching go down. As long as the local communities are involved, there is a win-win situation. If local communities take ownership of the animals and benefit from tourism, they will be at the forefront of protecting their wildlife,” he says with much conviction.

His efforts in conservation have seen him earn several awards and accolades over the years including the World Ecology Award for 2010 and the 2012 Lifetime Achievement Award for Ecotourism. He is currently a nominee for the 2016 Indianapolis Prize, recognised as the world’s leading award for animal conservation and given to an individual who has made extraordinary contributions to conservation efforts involving an animal species or group of species.

Family life…

Dr Western has been married to anthropologist Dr Shirley Strum for over 33 years. Dr Shirley has studied baboons in

Kenya for 42 years and worked with local communities. “Ours is a call of the wild,” he says rather humorously. “ Since we are both in similar line of work, we share a deep commitment and a passion for animals.

Dr Strum is also a professor of anthropology at the University of California at San Diego, where she teaches each spring. The couple met at a wildlife workshop at UON in 1973 where Dr Western was presenting his research work on Amboseli and Shirley was presenting her research on baboons in Gilgil. They have two children – daughter Carissa and son Guy, and both have followed in their parents’ footsteps and work and live in Kenya.

As we conclude this interview, Dr Western emphasises that one of his biggest satisfactions is seeing the growth of wildlife clubs in Kenya and seeing young Kenyans become wildlife enthusiasts and ambassadors.

“It would be great for future generations to have parks to enjoy, and with urbanization, I am sure they will become the biggest advocates for saving them. I would also love for Kenyans to see wildlife beyond tourism, to get involved ion the conservation of natural resources as envisioned by the late Prof Wangari Maathai and Kenya’s Vision 2030,” he says.

March 2016